My apologies for being absent from this space. I dropped a stitch, there, for a moment. I’m going to get back to my original deadline, which was to post a column every Sunday and every Wednesday.

There’s an essay I wrote for Manifest Station a couple of years ago - which I mentioned in my last column - and it’s something I’d like to revisit. Manifest Station has a deep bench of contributors (see link), and I was pleased to be given a guest shot. Reading over the piece now, though, I can see a different approach to the canvas. My original emphasis was on memory, looking through the keyhole, but I think it might have been more effective if I’d tried to evoke the baffled POV of childhood. Manifest Station is a flourishing venue, and what I wrote for them at the time is still solid. I’m just borrowing the recipe.

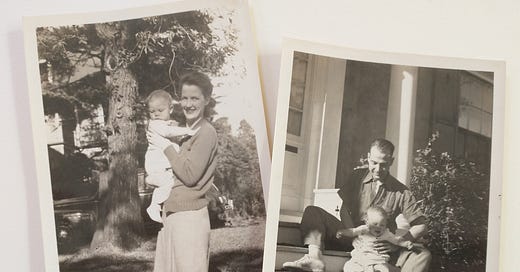

My grandmother’s house was haunted. Exaggeration for effect, I can hear you saying, but I mean it literally. I was little, four or five years old, and it made me deeply uneasy to spend the night there. It was dark, and full of heavy furniture, and even the paintings were left over from before the turn of the century. And it was chilly – not physically, but a kind of emotional chill, the nursery empty of children’s laughter. Not to mention, there were just the two of us, me and Gagy, my grandmother. Everybody else had abandoned ship.

As it turns out, this wasn’t far from the truth.

Every family keeps secrets. Often they’re benign, or not even what most of us would even call secrets, in the sense that they’re simply common knowledge: all the grownups know the story, and it doesn’t occur to them to explain it to the youngsters; this creates an air of mystery around something easily remedied. In my mother’s family, however, this wasn’t the case. The secrets were poisonous.

Gagy once told me that her older brother Tom had turned a dog loose on her when she was small. She still had the scars on her throat. This later got confused in my mind with learning her parents had divorced – divorced, in 1900 St. Louis, which was scandal enough, until my dad told me that he divorced her, and that their oldest son (that same Tom, again) had testified in his father’s favor, against his mother. Much later, she reappears in the family history, living an expatriate life in Menton, on the coast of France, just up the block from Monte Carlo, apparently a louche sort of exile, with rumors of sugar daddies. (The kind of thing I’d be dying to know, n’est-ce pas?) The point being, after all this time, that all the salacious details are lost. Nobody on my mom’s side ever said a word about any of it. My dad knew enough to say that Tom, the black sheep, was never able to bury the hatchet with his siblings, and when their dad remarried, his second wife was shunned, never accepted or acknowledged by his children.

Carrying this a generation further, like the House of Atreus, my mom later told me that her brother George had once hit her in the eye with a wood block from a toy building set. It caused a lasting injury. George and their middle brother Charlie had been having a battle with blocks, and when George was called on it, he argued, “She should have known, it was war.” This is an interesting alibi. Kids, guys especially, can be very legalistic, and George, as it happens, grew up to be a lawyer. My sister Bea came up with a much more disturbing narrative, many years on, which is that George bullied and abused our mom, on a regular basis. We can’t say for certain that it crossed the line into sexual abuse, but for sure it was emotional. The thing to emphasize, here, is that there was nobody to protect her.

Her father had died when she was seventeen. He had Parkinson’s, and he was an invalid in the last years of his life, and absent. Here’s another thing that remained hidden, long after. I don’t get it. Were they embarrassed by his illness? The whole thing bewilders me.

None of this is anything a four- or five-year-old could even begin to process. If you knew about it, how would you relate it to your own childish experience? A kid has no context, at least not for something so much larger than their own immediate reality. I knew something was wrong, at Gagy’s house, you could tell, but you couldn’t put your finger on it. My grandfather died before I was born, but his study – a big room on the south side of the house, with floor-to-ceiling bookcases, and a desk that allowed a lot of east light – stayed undisturbed, from his death until my grandmother gave up the house. For thirty years.

That house gave me nightmares back then, and it gives me nightmares, still. The familiar dread comes back. I’m alone, as always. The hallway is dark. Something lies in wait. It has no name, but I know its shape, just the other side of the door. I’ve never seen its face.

David, I read The School of Night with great interest. I believe I have a number of original letters written by your mother, if your mother was Clare Elizabeth Haskins Gates. The letters are written to her mother. I also have letters from her two brothers George and Charles written during the same time period. I would love to share these with you if you are interested. I can be reached at unioncounty@gmail.com if you are interested.