Operation Magpie

1944: THE NAZIS LAND IN MAINE

I spent childhood summers on Hancock Point, Maine, where my grandmother had a summer house. It was across Frenchman Bay from Bar Harbor, on Mt. Desert Island, but far from Gilded Age. It wasn’t fashionable or upscale or exclusive, it was pretty modest. And it wasn’t simply a cottage colony, either, people lived there year-round. It was a real community, not a Potemkin Village. One of those local families were the Fornis, and one of the Forni girls, Jeanie, used to babysit me. She was only a couple of years older than I was. Sometimes she took me down the road to her house. If her mom Mary was home, she was likely to be in the kitchen baking, which might mean fresh chocolate chip cookies. There’s a story about Jeanie’s mom Mary that I never heard until a long time after.

In late 1944, before I was born and Jeanie was about two, Mary was driving home one night, down the Point. She’d been playing cards at a girlfriend’s. It was November, and there was a light snow. She saw two guys walking up the road. She thought they were overdressed - like Wall St., she later said. They weren’t local, and given the time of year, they weren’t tourists, or summer people. She noticed their footprints, which came up through the woods from the West Shore, and that was odd, too. It still bothered her enough the next day that she contacted the sheriff’s office. It happened that deputy Dana Hodgkins’ son had also seen the two men the night before, and Hodgkins got in touch with the FBI.

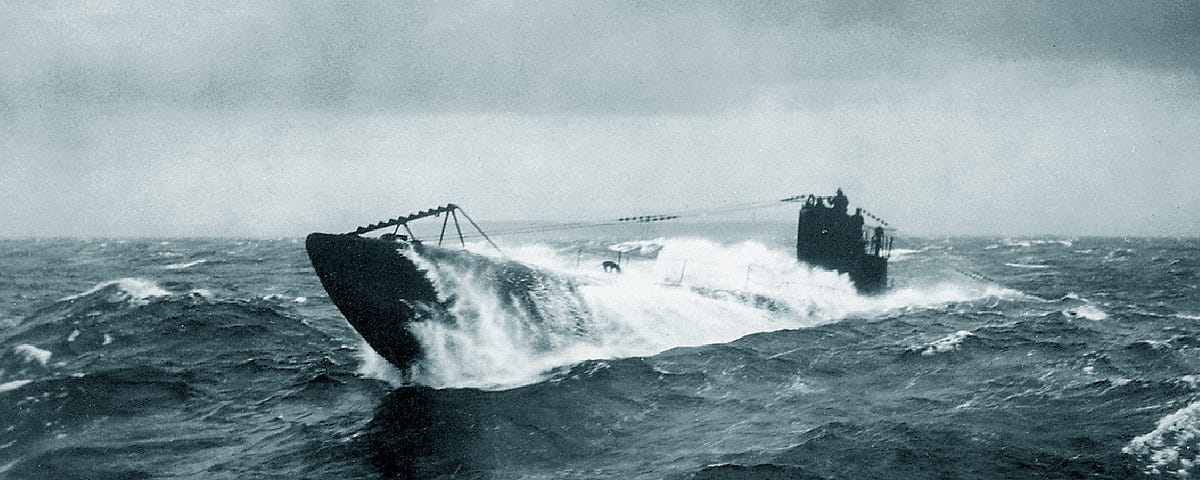

Now, remember, this was wartime. And as crazy as it sounds, those two guys walking up that snowy road in rural seacoast Maine were, cross my heart, actual Nazi spies, dropped off by a U-boat that had snuck in from the North Atlantic, and threaded through the islands and the shoals to a landing spot on the rocky shoreline, the same rocky ledges I knew from picnics, where we picked mussels at low tide, and lobstermen hauled pots. The water in the inlet is no deeper than twenty-five feet. You’d feel your way up that shallow, unfamiliar channel, with the boat submerged at periscope depth, and touch bottom once or twice. If you were that German skipper, you had balls of steel.

Their names were Erich Gimpel and William Colepaugh, and they’d been recruited to an operation code-named Elster. Gimpel was a German national, and a radioman with some history of undercover. Colepaugh was an American who’d deserted from the Merchant Marine, and gone to the German embassy in Lisbon, to renounce his U.S. citizenship. No spy-handler with any experience would have put the two of them together in the field, because Colepaugh was clearly a lightweight. And so it proved.

They slog up the Hancock road through the snow, five miles to Rte. 1, and flag down a taxi – what are the odds, in a nor’easter? – that lands them in Bangor, where there’s the train to Boston. Eventually, they get to New York. In the meanwhile, the sub, U-1230, torpedoes a Canadian freighter just off the coast, giving itself away as it slips back into the North Atlantic. The FBI is following up on the reported sightings by Mary Forni and the deputy’s teenage son Harvard Hodgkins. A previous Nazi sabotage mission on American soil, in 1942, had ended in the capture of eight infiltrators and immediate execution of six; nobody is under the misapprehension this won’t be a full-court press.

The two agents set up shop in an apartment on Beekman Place, and Gimpel tries to focus on the mission, buying parts to build a shortwave radio, sending Colepaugh out to take notes about shipping activity in New York harbor. Colepaugh is bar-hopping and chasing skirt. Gimpel is no monk, either, but after three weeks, just before Christmas, Colepaugh runs out on him, taking most of the money they were given by German intelligence to finance the operation. The magpie has flown the nest.

Worse than that. Colepaugh surrenders to the FBI, they take Gimpel down a few days later. Colepaugh sings, Gimpel is buttoned up tighter than a clam. The interrogators say Colepaugh is unstable, chatty, and over-shares; Gimpel is a pro, he’s facing the electric chair, he gives up nothing.

They were convicted and got the death penalty, Harry Truman commuted their sentences. They were later paroled. It’s really not much more than a footnote. There was some talk that Gimpel was somehow supposed to ferret out atomic secrets, but Germany knew next to nothing about the Manhattan Project, and misread its significance; Werner Heisenberg, back in Berlin, was doing his best to keep Hitler’s minister of production, Albert Speer, in the dark about the feasibility of a nuclear weapon. Gimpel and Colepaugh never made the big-time. It wasn’t in the cards.

I like the fact, though, of our brush with history, that Jeanie Forni’s mom, who made those great chocolate chip cookies, helped foil a Nazi plot. She saw two guys on a snowy night, with their footprints coming out of the woods, and smelled a rat. I admire her presence of mind.

A taxi - on Rt 1 - in 1944?

Wow, amazing story!